Explore Italy by place | region | time period

The Age of Metals » Bisceglie (Bari, Apulia)

Between the V and the III millennium BCE, the megalithic cultures spread mainly in Atlantic Europe (Brittany, England, Ireland, northern Spain) but also in the Mediterranean area (southern France, Italy). They are named after the megaliths (from the Greek mégas 'great' and líthos 'stone'), large stones used to erect great works. They are the first sign of a new will of Western man to raise works that can last in time.

The most common megalithic shapes are:

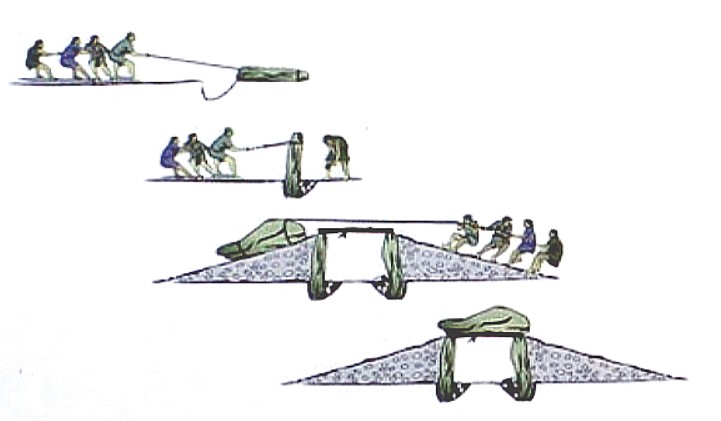

- Dolmen (word originates from the Celtic word Tolmen - dol='table', men='stone' - which translates as Stone Table) a sort of burial chamber consisting of two large vertical stones on which a flat rock table rests horizontally and rarely preceded by an entrance corridor (dromos) bordered by two rows of slabs driven into the ground. This trilite is the first example of an architectural structure consisting of an architrave (capstone) supported by load-bearing elements (two vertical stones).

- Menhir (from Breton men='stone', hir='long') a gigantic parallelepiped-shaped monoliths up to 20 meters high and stuck into the ground upright. It was believed that they cured fertility because the broad faces are oriented to east and west and always illuminated by the sun from dawn to dusk, it was a ritual function linked to the cult of the sun or the fertility of the Earth Mother goddess spread in the Neolithic; but it is more likely that they were the burial place of a leader or an important shaman. In Roman times they were used as road signs since they were located near crossroads.

- Cromlech (from Welsh Crom='curved' and lech='flat stone') are more menhir arranged circularly.

We know that the megalithic populations were not stable but, after long periods of time, they moved en masse toward other locations. Before to transmigrate they covered the tombs with mounds of earth and stones (specchie) to avoid the tombs were harassed and the buried bodies of their loved ones were violated.

In ancient times these prehistoric monuments were defined works of giants. They were landmarks and meeting places of encounter for communities coming also from distant lands on special occasions, such as their realization which could require the coordinated employment also of a hundred people.

The megalithic architecture is documented in Puglia by numerous dolmens and menhirs scattered throughout the territory. The popular imagination called them Houses of Giants (or fairies or devils), while they were often shelters in France of legendary characters such as Rolando and Gargantua.

In 380 CE the emperors Gratian, Theodosius I and Valentinian II promulgated the Edict of Thessalonica: this document proclaimed Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire. It was an implicit condemnation towards the worship of pagan religions which risked demolishing the megalithic works. Fortunately the people of Apulia found a compromise: the buildings would have been spared provided that iron crosses were placed on top of of some menhirs, while on the others were engraved crosses, to exorcise any residual pagan energy, and the name was changed to Hosanna.

Even today, rites that exorcise devils and witches are used during Palm Sunday in some villages and towns of the Lower Salento. For example, some farmers beat bundles of palms and olive trees blessed against menhirs, while the processions end near menhirs used as hosanna.

During the Middle Ages megalithic monuments continued to be objects of worship. The Church tried to repress pagan rites with a series of councils. But it was only after an edict by Charlemagne that many were destroyed.

From 800 to today it is estimated that 65 menhirs have been demolished.

The dolmen of Chianca, nestled in the countryside and surrounded by olive trees, was famous since the time of the Romans. It’s considered to be one of the most important in Europe and it’s also very well preserved. In 2011 it was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It dates back to the Bronze Age and belongs to the type of tomb with a wide corridor, composed of a burial cell and an access corridor (dromos).

Chianca derives from a dialectal expression from Apulia (chienghe) which means 'table' exactly like dol of the Celts of Lower Breton or planca of Latin. It undoubtedly refers to the main part of the monument, the slab forming the roof.

The dolmen is a total length of just under 10 meters and is formed by four large stone blocks which constitute the burial cell and other smaller that form a corridor (7.80 meters), which perhaps once was covered.

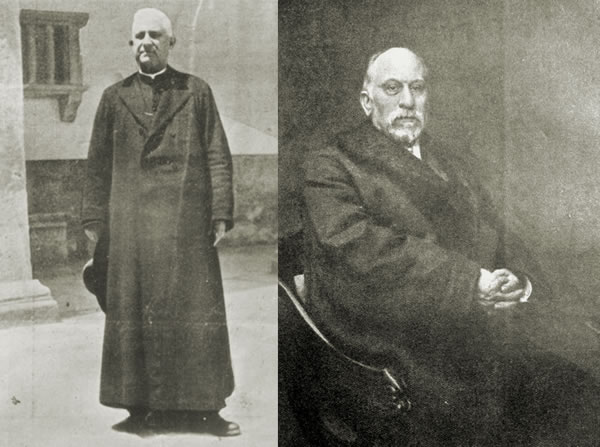

In 1909, a massaro had a conversation with the priest Francesco Samarelli about a stone hut located in a land of his master. Samarelli immediately advised Mosso, a archaeologist and senator of the Kingdom of Italy.

After a first reconnaissance in the farm of Lucietta Pasquale Berarducci of Bisceglie on August 3, the priest slowly reached the place with the senator on August 9. They were accompanied by a perennial shower, they walked through country roads with their feet sank into the grass. But in the end, they sighted the dolmen. It was still intact and hidden by the olive trees. For Mosso it capped off his archaeological expeditions and he always remembered it as one of the most beautiful days of his life. They also noticed piles of stone and soil covering the building, and realized that the local farmers had already removed everything before their arrival. Nevertheless, the excavations carried out have returned inside the burial cell numerous human bone remains dating back to 1200-1000 BCE, ox bones mixed with ashes and coals (undoubtedly the leftovers of funeral banquets consumed in honor of the dead) and a rich funerary kit consisting of small vases, necklace pendants, a fuselage, fragments of obsidian blade and flint, a bronze falera; while in the dromos some crockery blackened perhaps by the ritual fires and a jug.

The discovery had resonance in the national press.

Some indications suggest that the dolmen of Chianca was used for the practice of elaborate rites of passage:

- the burial cell (symbolic representation of the otherworldly dimension) had inside it dishes as well as bones of animals, which ideally served as foraging along the transit. In this sense, the dromos served as an anteroom for the funeral banquet;

- the dromos (ideally the path that the soul of the deceased had to take to reach the afterlife) is oriented towards the east, where the sun rises, where the day begins and then life;

- the fires lit along the corridor were perhaps to facilitate the transit of the deceased;

- the holes visible at the level of one of the vertical slabs had to allow the soul of the deceased to reach the burial chamber, so that it could be reunited with the body.

A curiosity: Angelo Mosso (Turin, 30 May 1846 - Turin, 24 November 1910) was an Italian doctor, physiologist and archaeologist, but is also remembered as the inventor of the first sphygmomanometer , still in use to detect blood pressure.

In order to know more, you can visit:

- Wikipedia: [1]

This page was last edited on 8 June 2024

Open in Google Maps and find out what to visit in a place.

Go to: Abruzzo | Aosta Valley | Apulia | Basilicata | Calabria | Campania | Emilia Romagna | Friuli Venezia Giulia | Lazio | Liguria | Lombardy | Marche | Molise | Piedmont | Sardinia | Sicily | South Tyrol | Trentino | Tuscany | Umbria | Veneto

Text and images are available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 4.0; - italystudynotes.eu - Privacy