Explore Italy by place | region | time period

Republican Rome » Bologna (Emilia Romagna)

The area where Bologna stands today has been inhabited since the 3rd millennium BCE. From the 9th to the 6th century BCE, Villanovan settlements from the Iron Age were present. They were located in a strategic position on the Italian peninsula, at the crossroads of trade routes between the north and south.

Etruscan cultural and artistic evidence has been found in Bologna and dating back to the 7th-6th centuries BCE. Here, the Etruscans founded Velzna ('fertile land', in Latin Felsina) in 534 BCE. It was a rich and flourishing city that became the capital of Etruria Padana. Between the 5th and 4th centuries BCE, Gallic tribes of the Boii arrived, and the Etruscans lost control of the city. Nevertheless, these two populations coexisted for about two centuries and eventually merged. The funerary stele of the Etruscan admiral Vel Kaikna belongs to this historical period.

The Margherita Gardens are an oasis in the heart of Bologna, covering 26 hectares of land. They were inaugurated in 1879 with the name 'Passeggio Regina Margherita' of Savoy (1851-1926), in honor of Italy's first queen, who visited them before their opening.

They originated as English-style romantic gardens in 1868 when the Municipality of Bologna decided to purchase land along the ancient city walls from Count Angelo Tattini. During the creation of the Margherita Gardens, an Etruscan burial ground rich in artifacts was discovered here, which are now preserved in the Civic Archaeological Museum of Bologna. Two of its tombs were reconstructed within the park.

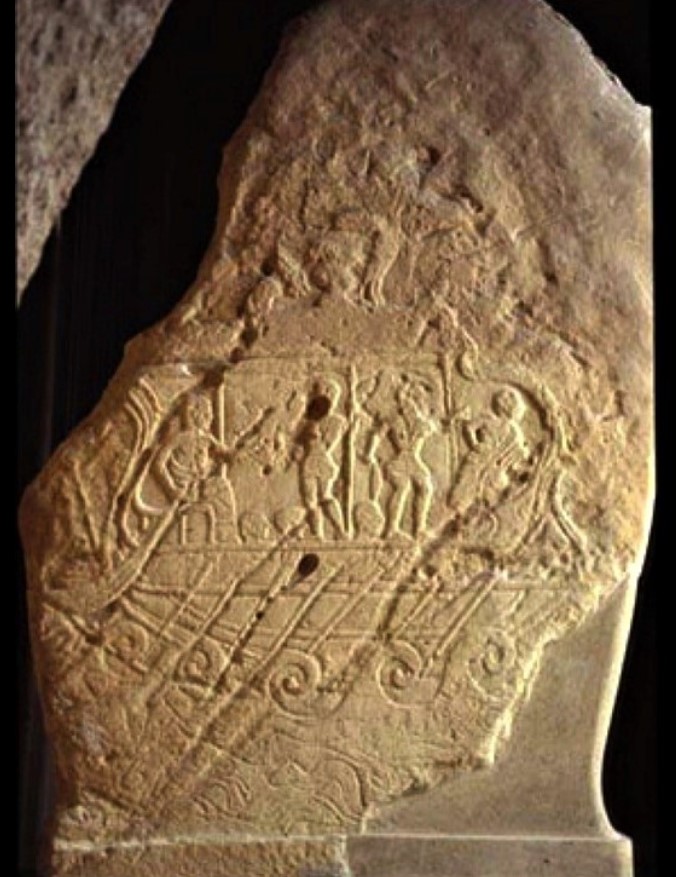

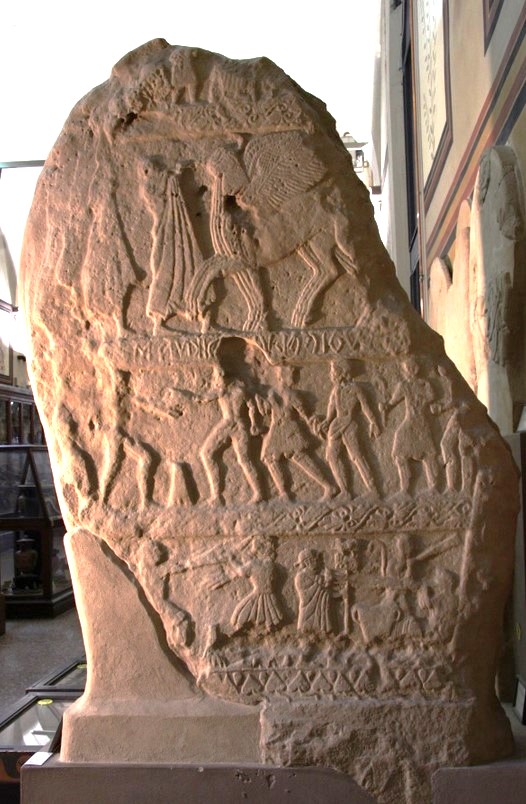

Among the various artifacts brought to light, there is the funerary stele of the Etruscan admiral Vel Kaikna. It is exceptional both for its size (2.42 meters in height) and for the low-relief decorations on both sides.

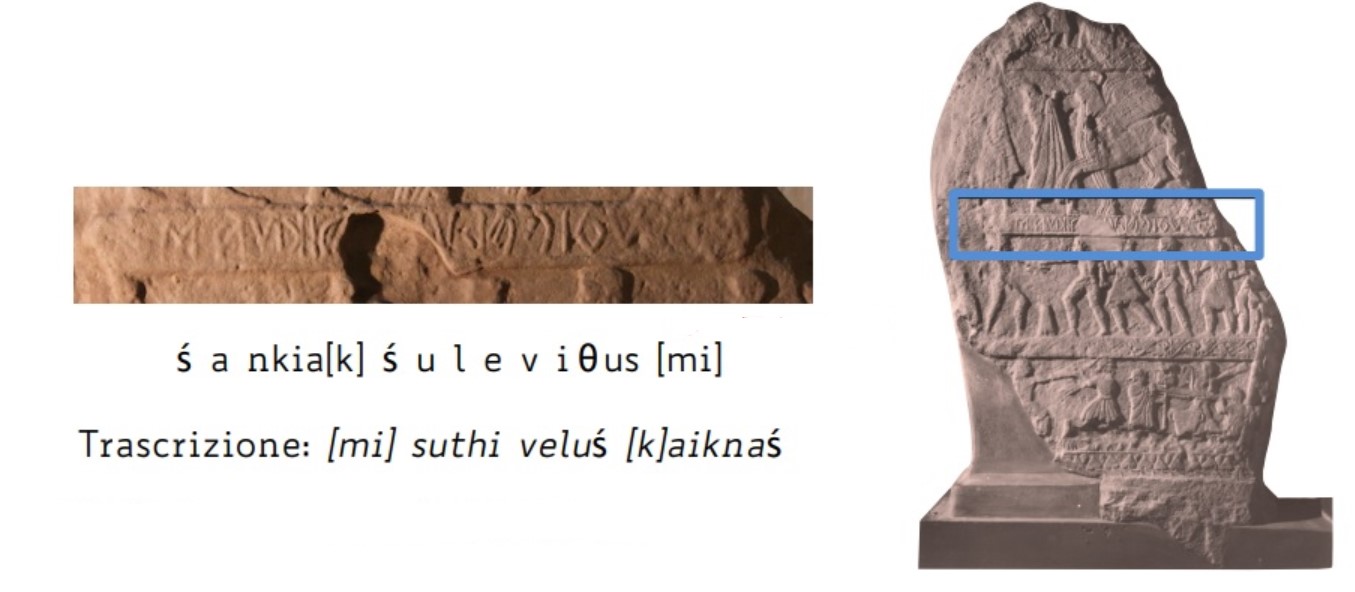

The main scene on the stele likely refers to the activities carried out by the deceased, whose name is known thanks to the inscription engraved on the other side of the stele.

(I am) Vel Kaikna's tomb

This is the stele of a legendary Etruscan general belonging to an important family of Felsina, an Etruscan admiral or navarch from the 5th century BCE.

On one side of the stele, the image of a large Etruscan warship sailing the sea is carved. You can see the helmsman holding the rudder at the stern, two armored warriors on the deck, and the lookout wearing a cloak and scanning the horizon at the bow. The bow is equipped with a ram. The sails are furled. Seven oars protrude from the keel of the ship, although only the heads of three rowers are visible.

The other side of the stele is divided into four bands by thin strips, which include, at the top, the deceased's journey to the afterlife in a chariot (quadriga) with winged horses and lituus players. Below, there are scenes of solemn athletic games, likely held in honor of the deceased, in the presence of prominent public figures. In the third register, on the left, a boxing match between two boxers is depicted, while on the right, two other contenders (prisoners) are being led to the arena by two attendants with lituuses. In the fourth and final register at the bottom, another boxing scene is shown, with judges of the contest and trumpet players.

This stele is important because it depicts an Etruscan ship from the 5th century BCE. Generally, we know about Etruscan vessels through Greek and Roman authors or through vases. Pliny the Elder (Nat. Hist. VII, 57; VIII, 209) states that the beak (rostrum) of ships was invented by the Etruscans, while Livy (Histories, XXVIII, 45) mentions linen sails and the types of wood used for constructing Etruscan ships: oak and beech for the hull and internal parts, and fir for the masts.

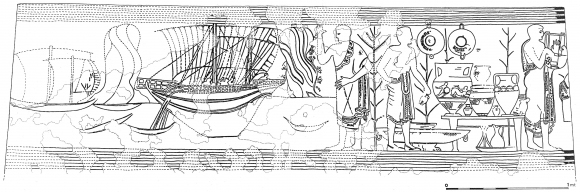

Another description of Etruscan ships is provided by the Aristonothos crater from 650 BCE, which was found in Cerveteri and is preserved at the Capitoline Museums in Rome. It may depict a clash between a Greek ship (on the left) and an Etruscan ship (on the right).

The Greek ship appears to be a war vessel with a flat hull, high stern, and a prow with a ram and apotropaic eye. Its crew consists of rowers and soldiers on deck. In contrast, the Etruscan ship seems to be a merchant vessel, equipped with sails, featuring a deeper and more curved hull, a pointed prow with a ram, a stern with a double rudder, and a central mast. The Etruscan crew includes warriors ready for combat on deck and a lookout stationed in the crow’s nest.

It is believed that initially (during the Villanovan phase) the Etruscans were inspired by Aegean and Phoenician ship models, but over time (during the Orientalizing and Archaic periods) their ships developed distinctive features. Etruscan ships appear to have had broad and capacious hulls, distinguished by a ram at the prow (or a particularly sharp prow) designed to strike enemy vessels, as well as to cut through the waves and improve the hull’s buoyancy. Thus, it is thought that these ships were hybrid in nature, combining commercial and combat characteristics. Iconography also suggests that Etruscan ships could have been equipped with a double deck (raised deck), a central mast, were steered by two rudders at the stern, and used square sails.

Later, starting from the 5th century BCE, the functions of ships became increasingly diverse, as evidenced by the merchant ship depicted in the Tomb of the Ship and the warship represented on the Vel Kaikna stele.

Then out of nowhere, men emerged from a galley ship Pirates. They surged forth out of the wine-dark sea, a group of Tyrsenians.

- Homeric Hymn to Dionysos. Epiphany at Sea: Dionysos and the Pirates.

The Tyrrhenians (or Etruscans) were considered pirates (from the Greek peiratès, 'one who attacks, one who goes on the offensive'). In antiquity, the profession of piracy was not considered disgraceful. Most of the time, it wasn’t even genuine acts of piracy but bellum piraticum (wars of privateering), similar to the actions of privateers in English and Spanish trade during the 17th-18th centuries. In Greek and Roman times, the phenomenon reached such proportions that the Romans were driven to launch a large-scale offensive against the pirates.

It has been hypothesized that Vel Kaikna held the position of commander of an Etruscan fleet in the Adriatic, defending the trade routes to and from Greece that were centered around the port of Spina.

The port city of Spina represented the maritime outlet for the Padanian Etruscans. It was about 80 kilometers from Felsina. Spina may have had a very close connection with the Greeks of Athens, as it was believed that the two peoples shared common ancestors in the Pelasgi. Between the late 6th and early 3rd century BCE, it was one of the most significant Etruscan ports in the Adriatic Sea and one of the most influential throughout the Mediterranean. During those centuries, Greeks, Phoenicians, Latins, Celts, and other Italic peoples made up the ethnic landscape of the Italian peninsula before the Roman conquests and subsequent dominance. The Greek historian Strabo recounts the gradual decline of Spina, which began with the arrival of Rome and the founding of Rimini in 268 BCE. By the time of Emperor Augustus, Spina had already faded into obscurity.

The search for ancient Spina among the marshes in the Po delta fascinated scholars and distinguished researchers since the Middle Ages, but every trace of the famous and prosperous maritime emporium described by Greek and Roman authors seemed to have been lost. The city remained buried in mud for centuries due to the flooding of the Po River and the subsequent advancement of the Adriatic coastline.

At the end of the 17th century, the Bolognese physician Gian Francesco Bonaveri was the first to hypothesize that the site of Spina was near the Valle Trebba, a valley close to Comacchio, as ancient artifacts occasionally emerged from that lagoon environment. However, his intuition was only confirmed three centuries later. In 1922, Spina was discovered near Comacchio by chance during drainage works. Thousands of tombs and over 4,000 richly furnished burial goods were found.

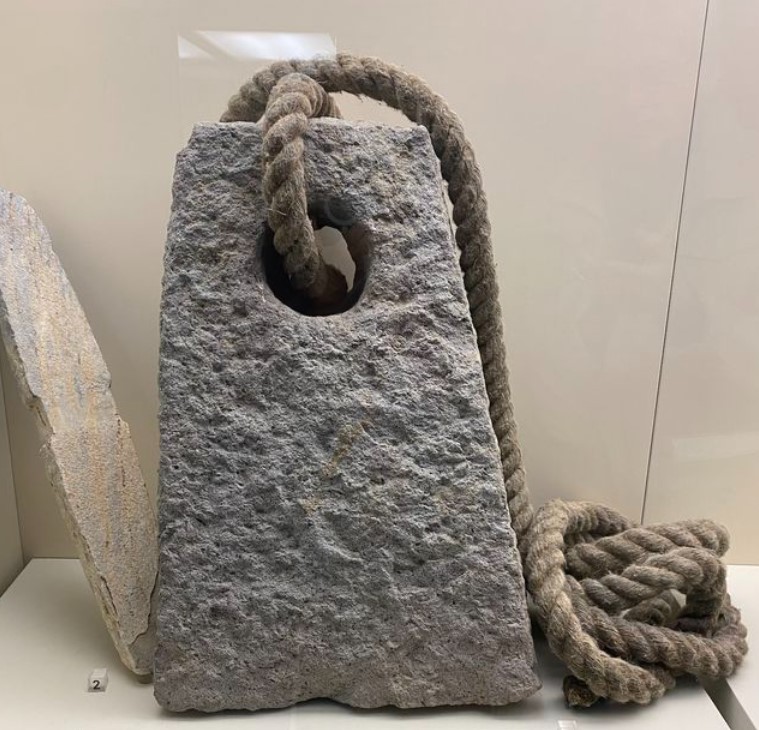

The reproduction of the ship is likely related to the activities performed during the deceased's lifetime. Indeed, Etruscan sailors were often buried with ship models (such as those from the Villanovan period found at Poggio dell’Impiccato, Tarquinia) to signify their desire to master the sea and sail with their own ship even after death. According to some scholars, the small boat models found in funerary contexts symbolize the sea voyage to the afterlife and do not provide significant information regarding the types of Etruscan vessels.

The sandstone stele of Vel Kaikna, dated around 450-420 BCE and discovered in the Necropolis of Giardini Margherita, is now displayed in the Etruscan room of the Civic Archaeological Museum of Bologna..

In order to know more, you can visit:

- Wikipedia: [1]

This page was last update on 10 July 2024

Open in Google Maps and find out what to visit in a place.

Go to: Abruzzo | Aosta Valley | Apulia | Basilicata | Calabria | Campania | Emilia Romagna | Friuli Venezia Giulia | Lazio | Liguria | Lombardy | Marche | Molise | Piedmont | Sardinia | Sicily | South Tyrol | Trentino | Tuscany | Umbria | Veneto

Text and images are available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 4.0; - italystudynotes.eu - Privacy