The Ancient Rock Art of Val Camonica: A Journey Through Time

The Neolithic Age in Italy » Camonica Valley (Brescia, Lombardy)

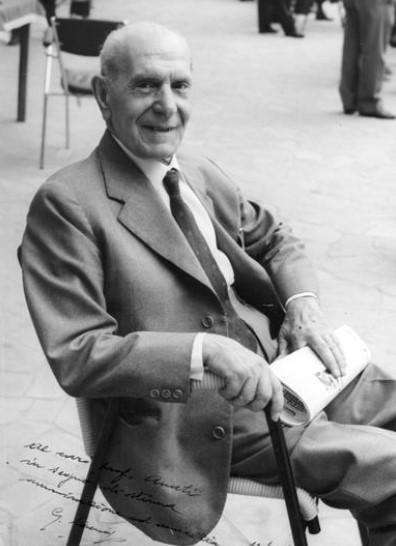

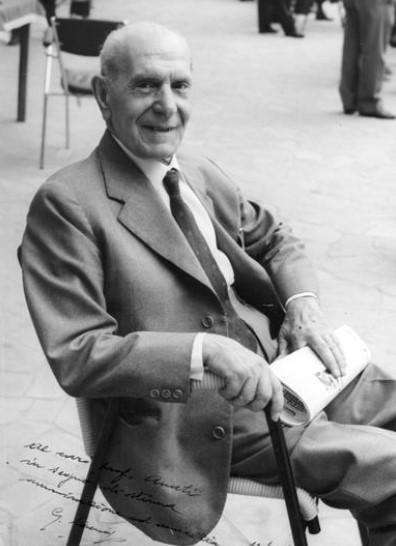

In 1909, a young geologist and mountaineer, Gualtiero Laeng (1888-1968), discovered two prehistoric engraved boulders at Cemmo, near Capodiponte in Valcamonica. Since then, many other scholars have arrived in the valley to search for more engravings and were amazed to find that these rock carvings were not confined to a single site but spread throughout the entire alpine valley for about 90 km.

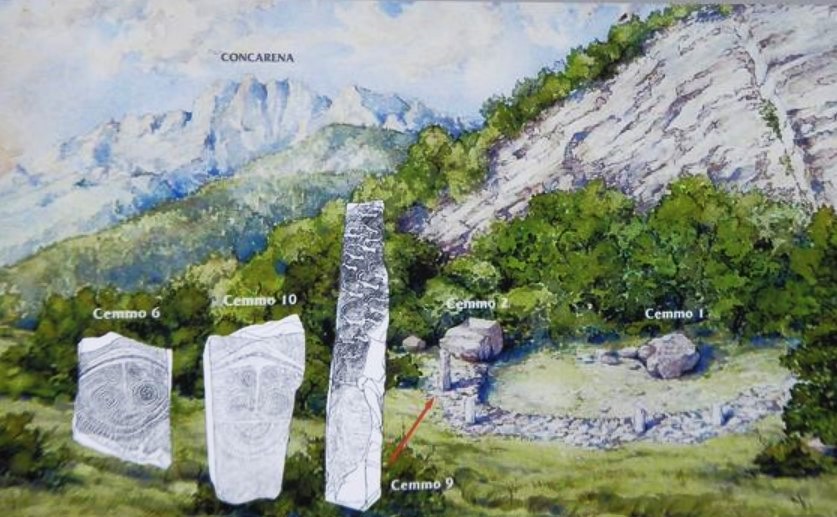

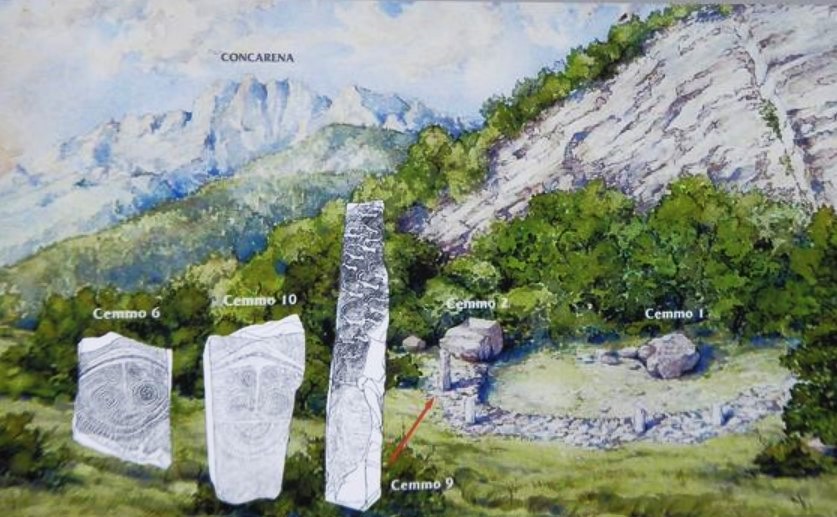

Hypothetical recostruction of the Cemmo Sanctuary during the Roman period. Several Chalcolithic steles still stood on the wall that enclosed the area around the Cemmo rocks (drawing P. Dander). Under, the site today [VIEW].

Laeng had discovered the rock art of Val Camonica, which had been hidden by woods and vegetation for over 10,000 years.

An example of how the vegetation continue to take over the territory covering the stained stones.

While the great civilizations of Egypt and Mesopotamia were developing, the Paleolithic tradition of rock engravings and paintings was spreading in the Mediterranean area. Some examples include those in Fezzan and the Algerian Sahara in North Africa, and those from the Bronze Age in Liguria and the alpine and subalpine regions of Val Camonica.

The Val Paghera (Vezza d'Oglio) and the Baitone Mountains

La Val Camonica (Valcamonica o Valle Camonica) is one of the largest valleys of the central Alps, in eastern Lombardy. Its ancient history begins about 15,000 years ago with the end of the last glaciation, when a 90 km long glacier melted, creating the valley. Between the 8th and 1st millennium BCE, some people settled here. They were the Camuni (from the Latin Camunni), a population we know little about except for their petroglyphs, who made their land the largest rock art center in Europe and the first prehistoric site included in the World Heritage List in 1979.

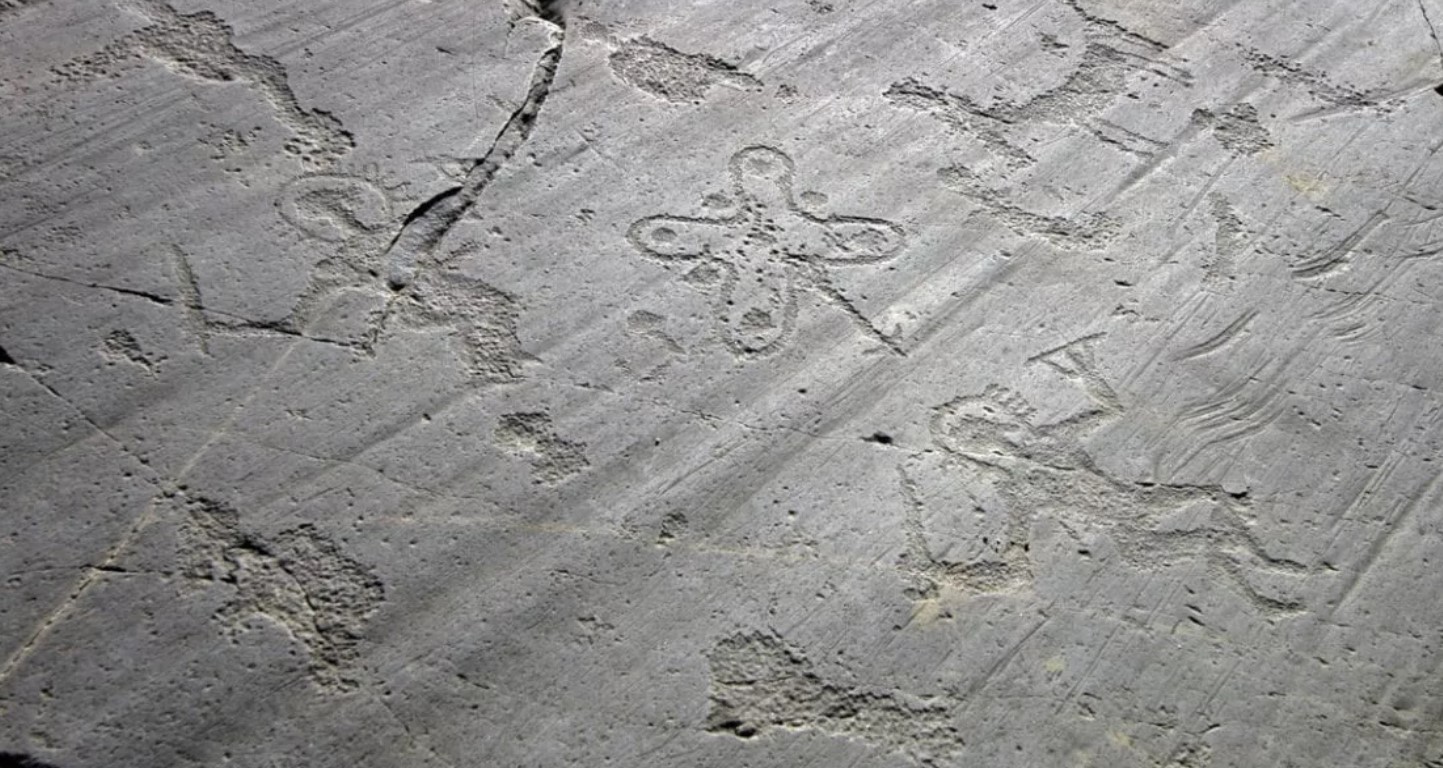

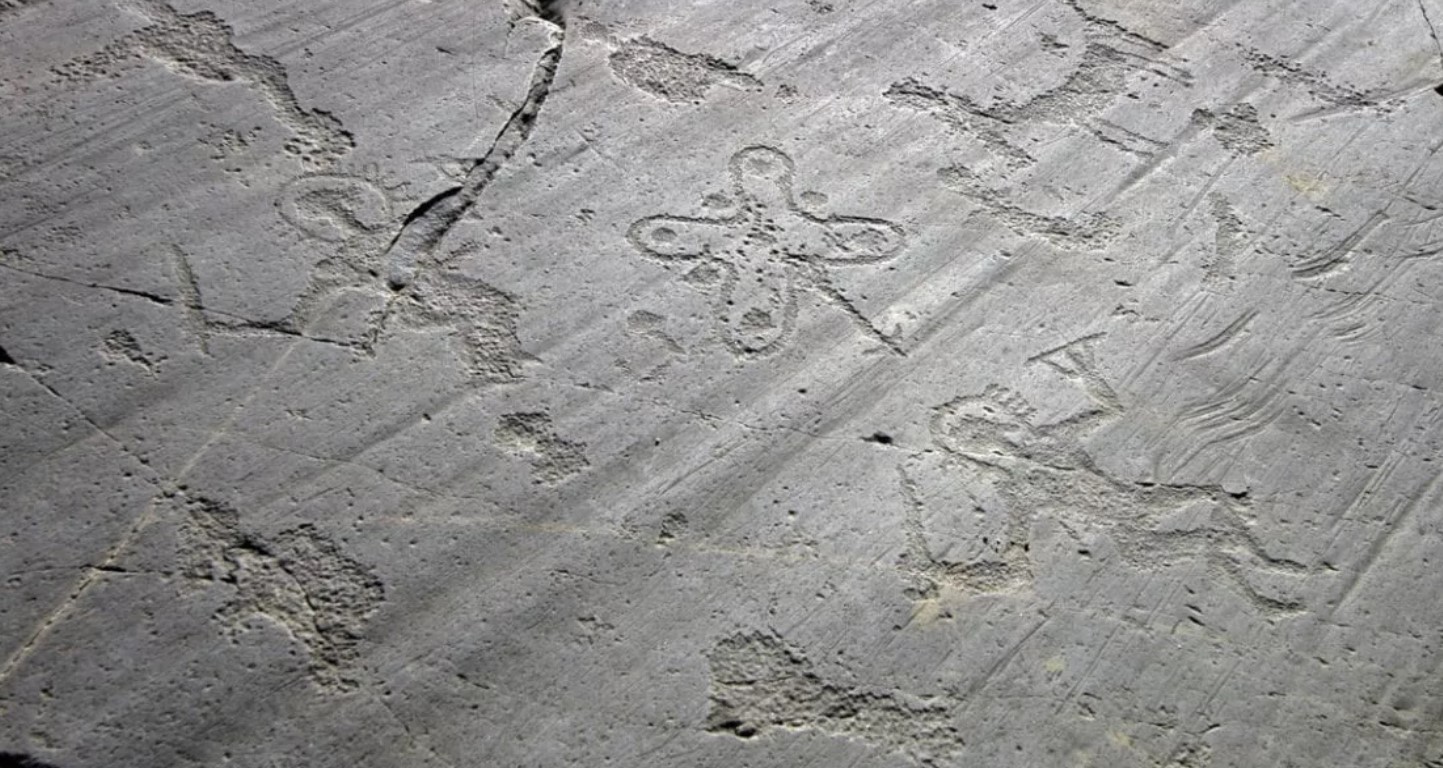

The camuna rose is one of the most famous rock carvings in Val Camonica. This symbol has been found 92 times among the 300,000 rock carvings.

These engravings were executed on over 2,500 rocks on both sides of the valley, depicting the daily life, customs, and traditions of this prehistoric alpine population. They feature scenes of hunting, dueling, craft activities, weapons, symbolic motifs, and inscriptions.

The last rock engravings date back to the Roman and medieval periods. Indeed, towards the end of the 1st century BCE, Val Camonica was annexed to the Roman Empire. After its conquest by the troops of the proconsul Publius Silius Nerva in 16 BCE, the city of Civitas Camunnorum (now Cividate Camuno) was founded. It had a forum, baths, a theater, and an amphitheater. Not far away was the necropolis, and not too far away (in Breno) was its sanctuary dedicated to Minerva (1st century CE), one of the largest in the Alps. The sanctuary was destroyed by a fire in the 5th century CE, when the Christianization of Val Camonica was well established, and its ruins were definitively buried with mud and debris for centuries by a flood in 1200.

It was discovered by chance in 1986 during an excavation for the sewer system and opened to the public in 2007; inside, a marble statue of the goddess was found in 2000. The sanctuary was founded by the Camuni in the 5th century BCE near the Oglio river because it was linked to the beneficial cult of water. The Romans built their structure on top of it.

Statue of Minerva Hygieia (from Greek hygieia, meaning 'saving', 'protection of health'). This goddess was chosen because she was one of the most influential deities in Celtic and alpine environment. The goddess with the left arm held a lance while with the right one pointed forward she received votive offerings. The breasts are covered by the invincible squamate aegis, adorned with the head of the gorgon Medusa; the helmet presents a sphinx.

National Archaeological Museum of the Valle Camonica, Cividate Camuno, Brescia.

The ages of the petroglyphs can be distinguished based on the subjects depicted, which change over time:

- The Upper Paleolithic has the oldest engravings showing wild animals such as elk and deer, probably carved by nomadic hunters.

Rock carvings of deer

- The Neolithic (5th millennium BCE) introduces figures connected to agricultural practices and anthropomorphic figures called "orants," men with legs and arms bent at right angles in the act of 'praying.'

The prayerful men

- In the Copper Age (IV-III millennio BCE) (4th-3rd millennium BCE), the engravings are mainly on steles or menhirs found within ceremonial and cult centers.

Some menhir at MUPRE - National Museum of the prehistory of the Valle Camonica, Capo di Ponte, Brescia

During this period, the Camuni discovered metallurgy, plowing, and wheeled transport, as evidenced by images of weapons or ornaments, plows drawn by oxen, and carts with wheels.

- In the Bronze Age , the first armed figures appear, including warriors wearing some kind of helmets.

Warriors with helmets

- Almost 80% of Camunian art engravings belong to the Iron Age (1st millennium BCE). They depict scenes of dueling, riders sometimes balancing on horses,

deer hunting scenes where a man with a long spear strikes the deer assisted by a dog recognizable by its curled tail. Sometimes only the spear appears, hitting the animal. There are also waterfowl, footprints, the Camunian rose, plowing scenes, and carts drawn by equids.

An engraving depicting a four-wheeled cart pulled by equidae (Iron Age, first half of the first millenium BCE), Valcamonica

The basic structure of this cart is not very different from that of some of the carts still use in Valcamonica today. The long rectangular body and small wheels do, in fact, make it ideally suited to the narrow mountain tracks. A front forak strengthens the shafts to which the two horses are yaked. The wheels have four internal spokes. The fact that the cart has no bottom shows that the load was placed directly on the frame and held in place with ropes. The cart is drawn as if seen from above, while the wheels and horses are as if seen from the side. The animals in the rock carvings are not always yoked, but where they are depicted as yoked it is possible to trace the transformation from oxen to horses. From the drawings it is not possible to get any clear idea as to what the carts were used for as they are usually isolated rather than part of a scene.

Finally, there are the buildings that were initially interpreted as stilts, while today we think of alpine houses in stone and wood.

This panel illustrates a series of constructions (dwellings, granaries, temples) superimposed over a hunting scene; thus, a number of these figures (dogs, deer) appear within the structures, even if they were made years before by another person. At times an anthropomorph materialises inside the buidings, arguably representing a simulacrum or statue of a divinity, but without giving any clue as to the function of the edifice. Maybe the constructions were superimposed over the hunting scene in order to place events around the village in perspective: hunting on foot or horseback, armed combat, work and religious acts.

The 'Rock of the Five Inscriptions' at Campanine di Cimbergo, as it presented itself at the time of its discovery (by Marro 1935)

These engravings testify to the contacts the Camuni had with neighboring populations, including the Etruscans, who controlled much of the Po Valley and the alpine populations around the 5th century BCE. Traces of Etruscan cultural influence remain in the Camunian alphabet, used in almost two hundred inscriptions, which is very similar to the northern Etruscan alphabets, and in the rock art itself.

By the 3rd century BCE, Celtic populations arrived in Italy from transalpine Gaul, settling in the Po Valley and coming into contact with the Camunian population, as evidenced by the presence of Celtic deities such as Cernunnos among the rock engravings.

The God Cernunnos (the end of the 6th century-early 5th century BCE), Valcamonica

This panel illustrates a large figure with peculiar attributes interpreted as the god Cernunnos and accompanied by a praying figure. The deity has deer antlers on his head, wears an armlet on his right arm and holds a knife. From his body a sinuous being comes out. This detail has been explained sometimes as a water bird headed solar boat and some others as a snake. In the Celtic world beyond the Alps some late representations of Cernunnos show the god sitting down cross-legged, wearing armlets and holding a knife, surrounded by domestic and wild animals. A famous image of him is the one on the Gundestrup cauldron (Denmark), dating back to the first half of the 1th century BCE.

- The Romans conquered the valley in 16 BCE. Christianity spread in the valley, and some sanctuaries were dismantled or destroyed. Examples include the one reported by Gualtiero Laeng in 1909 and the Roman sanctuary of Minerva, which was not rebuilt after the fire. Although the great cycle of Camunian art ended, the practice of engraving rocks continued with different elements in the Middle Ages.

Christianity, which arrived in Val Camonica at the end of the Roman Empire, spread among the population in a superficial and not entirely orthodox manner, so much so that the Camunian populations would have celebrated cults dedicated to pagan deities until the 9th century. For this reason, various laws had been enacted since ancient times to punish heresies. The Statutes of Val Camonica of 1498, for example, punished sodomy and diabolical heresy with burning.

Men and demons by Nathaniel Crouch, London, 1688.

In Europe, from the mid-15th century onwards, in religious debates regarding heresy and witchcraft, the figure of the witch and the reality of the Sabbath began to impose themselves as concrete threats to be fought without delay. Much of the beliefs and popular customs that retained the imprint of ancient pagan myths inevitably merged into the vast magical-diabolic repertoire of the inquisitors.

As this trend progressed, it was mainly the alpine populations that attracted the attention of inquisitors and demonologists. The isolation in which the inhabitants of Val Camonica lived, their social conditions, and the habits that came from these, combined with illnesses and physical deformities due to diseases, generated suspicion and fear in visitors, imbued with heavy prejudices. Of particular importance are the witches of Tonale, present in various Camunian and Solandrian legends with an ancestral and folkloric background, reaching a number of 2,500. It is said that on this mountain in the 16th century, during June, on Thursdays and Saturdays, witches' meetings, the so-called Sabbaths, were held. Mothers encouraged their young daughters to draw crosses on the ground and spit on them while shouting disgusting words. This ritual would make the devil appear on horseback, who would escort them to the top of Mount Tonale, where they participated in huge banquets. In exchange for their renunciation of Christianity, they obtained beauty and youth.

Gualtiero Laeng (1888-1968)

In recent years, a dozen very interesting paintings have been identified, revealing another aspect of this ancient alpine population.

In order to know more, you can visit:

- Wikipedia: [1]

This page was last update on 24 July 2024

Information:

- Address: NATIONAL PARK OF ROCK CARVINGS AT NAQUANE - Capo di Ponte (Valle Camonica - BS), Naquane

- Time period: 8th-1st millennium BCE