Explore Italy by place | region | time period

The Age of new people in Italy » Turin (Piedmont)

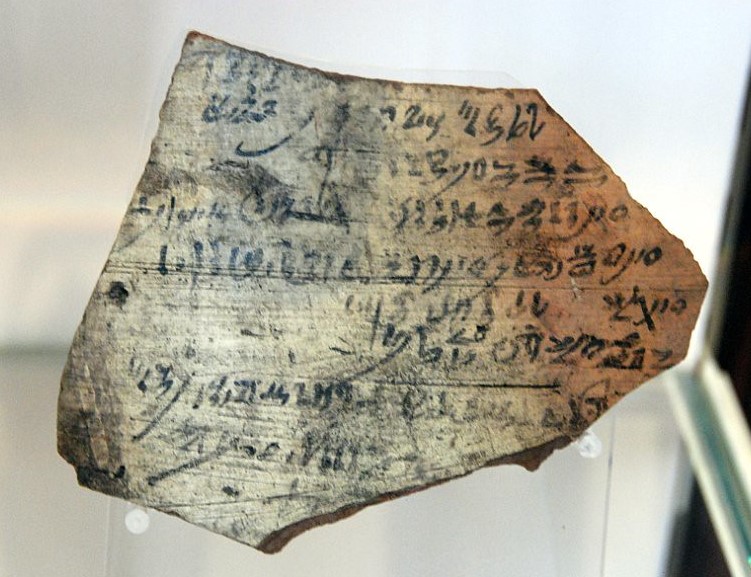

An òstrakon (plural: ostraka) is a piece of pottery or stone, usually broken from a vase or other earthenware vessels, used as a writing surface in ancient times. The term comes from the ancient Greek and means "shell" or "earthenware pot." Ancient people used these fragments because were abundant, durable, and inexpensive, making them a convenient medium for writing.

Ostraka can contain inscribed words, graffiti, or other forms of writing. Therefore, they are considered important epigraphic testimonies in archaeology, providing valuable clues about the period in which the piece was in use. Many ostraka have been found in Greece and Egypt.

In Classical Athens, when the decision at hand was to banish or exile a certain member of society, citizens would cast their vote by writing the name of the person on a shard of pottery. The votes were counted, and if unfavorable, the person was exiled for a period of ten years from the city, thus giving rise to the term ostracism. Ostraka provide archaeologists with evidence of events narrated by Greek historiography. For example, those found in Athens with the names of Cimon and Themistocles confirm Plutarch’s account that the two political figures were ostracized. Some scholars suggest there were more bizarre uses for these shards, such as when ancient Greeks exiled their enemies using ostraka and later used these broken pottery shards to wipe themselves, “literally putting faecal matter on the name of individuals,” to curse the exiled individual by soiling their name.

Today, many Egyptian ostraka are housed at the Archaeological Museum in Turin, the oldest museum in the world dedicated entirely to Egyptian culture and the only museum besides Cairo's wholly dedicated to Egyptian art and archaeology.

Among the various artifacts displayed in the museum, some come from Deir el-Medina. It was an ancient Egyptian workmen's village discovered at the end of the 19th century. Temples and tomb builders, architects, artists, and craftsmen lived there with their families and worked on the tombs in the Valley of the Kings during the 18th to 20th Dynasties of the New Kingdom of Egypt (ca. 1550–1080 BCE). Around five thousand ostraka of assorted works of commerce and literature were found in a well close to the village. We can say that the artists dabbled in painting on ostraka or used them for everyday purposes.

In ancient Egypt, anything with a smooth surface was used as a painting or writing surface. Ostraka were discarded material and therefore cheap, used for writings of an ephemeral nature such as messages, prescriptions, receipts, students' exercises, and notes. Alternatively, Egyptians used limestone flakes because they were of a lighter color. Thanks to ostraka, we know texts which in other cultures were lost, from the medical to the mundane. Through these, we today know aspects of their everyday life that would otherwise be unthinkable compared to literary treatises preserved in libraries. For example, we know that the workmen and inhabitants received care through a combination of medical treatment, prayer, and magic. Or that the "water carriers" were people who were tasked with bringing sacks of water to the village where each household could receive a quarter to a half of a sack, 96/115 liters of water per house.

Egyptian painters always adopted fixed forms and followed the same strict rules for centuries when the subject to be represented was very authoritative: for example, the gods, the pharaohs, or the queens, the great priests, and the aristocrats. In these cases, the artist’s intent was not to show their physical appearance but to highlight their importance. But there are other paintings, such as those of animals or the 'Acrobatic Dancer' arched in the position of the "bridge," which transgress the strict rules. This happened when the painter had to depict minor characters, so it was not necessary to create a self-textured image but one with great naturalness. Therefore, the rules were only mandatory for the representation of free men, nobles, powerful individuals, and the sovereign and his family. The painter was left more freedom of expression for the representation of everyday reality, the simplest and most humble, which did not impose the idealization of people's characters.

In order to know more:

- Wikipedia: [1]

- Toilet hygiene in the classical era BMJ 2012; 345 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e8287 (Published 17 December 2012)

This page was last edited on 29 June 2024

Open in Google Maps and find out what to visit in a place.

Go to: Abruzzo | Aosta Valley | Apulia | Basilicata | Calabria | Campania | Emilia Romagna | Friuli Venezia Giulia | Lazio | Liguria | Lombardy | Marche | Molise | Piedmont | Sardinia | Sicily | South Tyrol | Trentino | Tuscany | Umbria | Veneto

Text and images are available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 4.0; - italystudynotes.eu - Privacy