Explore Italy by place | region | time period

Republican Rome » Populonia (Livorno, Tuscany)

Populonia was one of the most important Etruscan city-states, with an economy based on maritime trade and iron production. The city’s development was heavily influenced by the proximity of the island of Elba, renowned for its iron mines. Maritime trade flourished through intense interactions with various countries, including Greece, Libya, Magna Graecia, and the Iberian Peninsula.

They [Etruscans] live in a region that produces everything and, by engaging in work, have fruits with which they can not only eat enough, but also enjoy a life of pleasure and luxury.

- Diodorus Siculus (I century BCE).

The name Populonia means ‘the city of Fufluns’. It was written during the Hellenistic period using the Etruscan letter f, which was introduced at that time. Before that, the Etruscans and Romans used the letter p, resulting in spellings such as Pupluna or Populonia, but the pronunciation was likely Fufluna. The name derives from the Etruscan word puple or fufle, meaning ‘vine shoot’. Fufluns was the Etruscan god of wine and drunkenness, similar to the Greek god Dionysus or the Roman Bacchus, and was the protector of the city.

To understand the deep connection between this ancient people and wine, consider the following points:

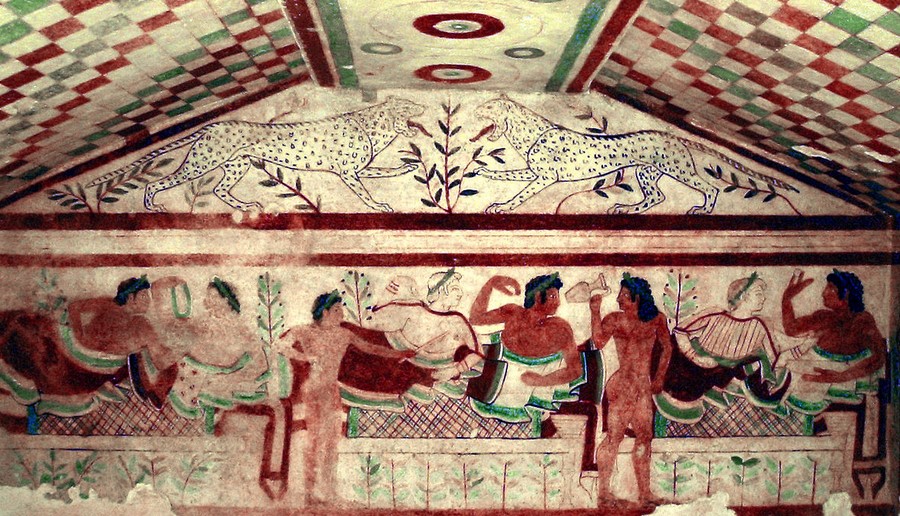

Viticulture was not a specialized activity during the Etruscan period. Vines were mixed with other crops like cereals, olives, fruit trees, etc. The wine was concentrated and very alcoholic. Since losing control during banquets and symposia was considered inappropriate, it was diluted with water to mitigate its effects, following Greek customs. The wine was also flavored and sweetened to cover defects due to limited production and preservation techniques.

The wine was brought into the hall in storage amphoras and mixed in a krater with water, cold or hot depending on the season, with added honey, herbs, flowers, spices, and resins.

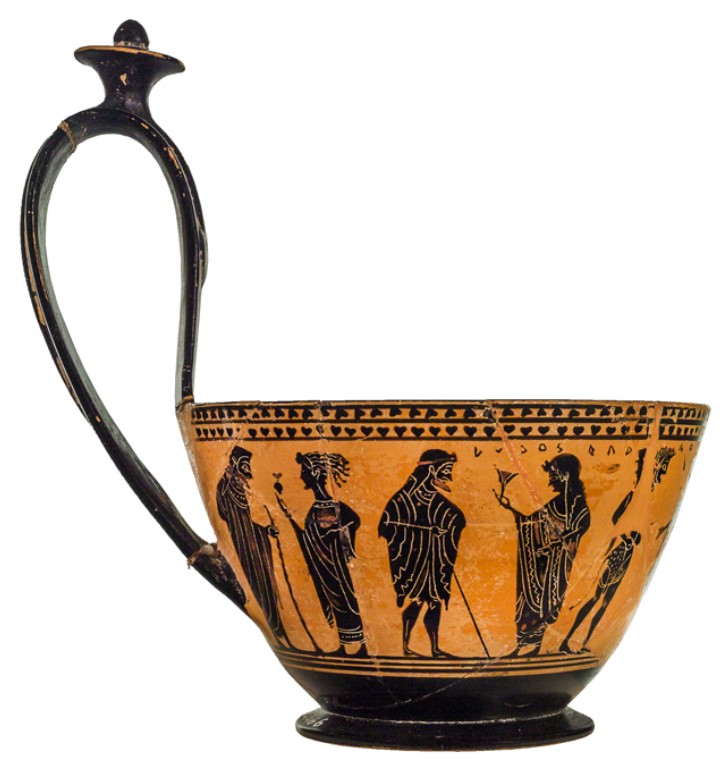

The various objects used for wine and the table were made of ceramic or bronze. They are known by Greek names because their Etruscan names are often unknown: krateres (wine krater), hydria (large amphora for water), situla (small buckets containing water), kyathos (Etruscan cup later widespread in the Greek world, used for both drinking and drawing).

Kyathos with Black-Figure Decoration, Vulci, ca. 520 BCE. Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia, Rome.

Twelve deities appear on the bowl, arranged in pairs. This scene possibly references the Anthesteria festival in Athens, dedicated to Dionysus (the god of wine). An inscription on the rim of the kyathos is partially legible: "Ludos egraphsen doulos …," which translates to "The enslaved person Lydos painted …" Thus, Lydos was possibly an servant of Mydea or originally from Myrina. In any case, the inscription aimed to celebrate his skill.

Strabo claimed that Populonia was the only Etruscan city built on the sea. Some scholars disagree because Etruscan coastal cities were 5-10 km from the sea for security reasons. The Etruscans were feared in the Mediterranean as pirates and knew how to defend themselves. The confusion arises from considering some coastal cities as Etruscan, but they have different origins. For example:

Given its importance, it is assumed that Populonia was one of the twelve cities of the Etruscan Dodecapolis, the main city-states that were part of Etruria, but there is no historical document confirming this.

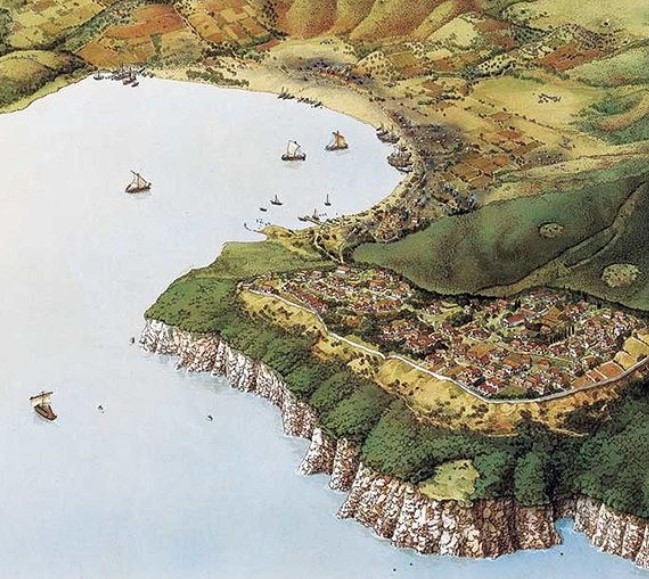

Populonia stood dominantly on one of the promontories forming the Gulf of Baratti, a natural harbor that was a mandatory stop for navigation. From there, it controlled the bay and the passage to the island of Elba. The natural mineral wealth of the Tyrrhenian and insular Tuscany was one of the main reasons for the Etruscans' prosperity. The Etruscan aristocracy accumulated exceptional wealth, including precious products from the East, through the trade of raw and processed minerals.

Elba was already famous in antiquity for its abundant deposits. It was probably the main site for processing extracted material in the early centuries. Thus, furnaces arose that melted the minerals with high flames day and night. As Aristotle narrates, Greek sailors gave the island the appellation Aethalia (spark) due to the numerous fires lit for smelting activities visible from the sea in the distance.

The coastal area from today's Bay of Baratti to San Vincenzo was populated by several small settlements since the Bronze Age (12th-10th centuries BCE) that worked minerals from the hinterland (mainly copper) and those unloaded from ships shuttling with Elba (mainly iron). During this period, the Tyrrhenians began to cultivate wild vines, produce wine, and trade it along with their other artisanal products.

The Gulf of Baratti thus became a true seaport, a crossroads between the Tyrrhenian Sea routes connecting Sardinia and Corsica with Etruria and, above all, a meeting place for influences from the rest of the Mediterranean.

At the beginning of the Iron Age (9th century BCE), a process of settlement aggregation began, making the one on the Populonia promontory the most important and populated. Based on the oldest finds in the necropolises, we can attest to the city's foundation around 900 BCE.

From the second half of the 8th century BCE, Populonia seems to have experienced a recession, perhaps related to the development of nearby Vetulonia.

In the mid-7th century BCE, local production of wine ceramics is attested in great quantity in Etruscan tombs of the period. This could be because Etruscan society was very advanced, and the demand for wine became increasingly demanding. Both local and imported wines were consumed. The increasing demand for different quality wines led to the development of overseas trade, primarily directed towards the Celts of southern France.

The wealthy Etruscan cities became a significant market for Greek ceramics, so Greek artisans included Etruscan forms in their production to meet the tastes of their best customers.

In the early 6th century BCE, Populonia experienced its peak thanks to iron. The large amount of wood needed to fuel the blast furnaces on Elba must have caused rapid deforestation, leading to a crisis in the activity. To offset the transportation costs of wood from the mainland, it was decided to move the processing plants to the continent. Thus, the Etruscans began to transport the metal by ship to Populonia, where there was abundant wood. The raw ore arrived from the nearby Elba mines, was smelted in powerful furnaces, and worked by skilled workers. The products were traded around the Mediterranean, while semi-finished goods were completed in other Etruscan cities.

Tomb materials from this period show a significant concentration of products from Eastern Greece, indicating that relations with this area played a relevant role in shaping local culture and artistic craftsmanship.

Thanks to its metallurgical industry, Populonia hosted thousands of inhabitants. The city formation process was complete. Populonia was divided into a lower and an upper part. The lower city, outside the walls, included the port, various metallurgical activities, and necropolises. The upper city, on the promontory's summit, housed the acropolis, temples, and domus.

It was equipped with an imposing wall. The acropolis and the settlement were defended by a first wall, while a second wall protected the industrial districts near the port. These expanded and extended over the older necropolises, leaving a significant amount of iron slag from metallurgical activities.

Between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE, Populonia became one of the main centers of mining and metallurgical industry for the Etruscans, alongside Volterra. It was also the Mediterranean's principal center for hematite processing, a type of iron ore abundant on Elba.

From the mid-5th century BCE, Populonia, which seemed unaffected by the recession that hit the southern Etruscan cities, was characterized by the presence of high-quality Attic vases, including a rare fragment of a white-ground kylix attributed to the Villa Giulia Painter, and local bronze workshops that made banquet vessels and furnishings.

The 4th century BCE is not remembered for particular historical events but for a servant known as the Baratti Man in Chains.

In 2016, an African chained enslaved person (the Man in Chains), according to anthropological analyses conducted, was found in a 4th century BCE tomb among the dunes of Baratti near the beach. He had somehow arrived through unknown routes in that corner of Etruria. He might have been a prisoner captured in some battle. His height and strong build determined his fate: a servant condemned to hard labor, with his feet locked in chains connected by leather straps to a collar, allowing him to work with his hands but never to be free. He died and was buried with the chains still on his ankles and the iron yoke on his neck. The unfortunate man lived in a cruel environment that evidently the surrounding community perceived as normal if they didn’t even bother to remove the irons before the final burial. Such conditions must have been widespread, perhaps more than we can imagine.

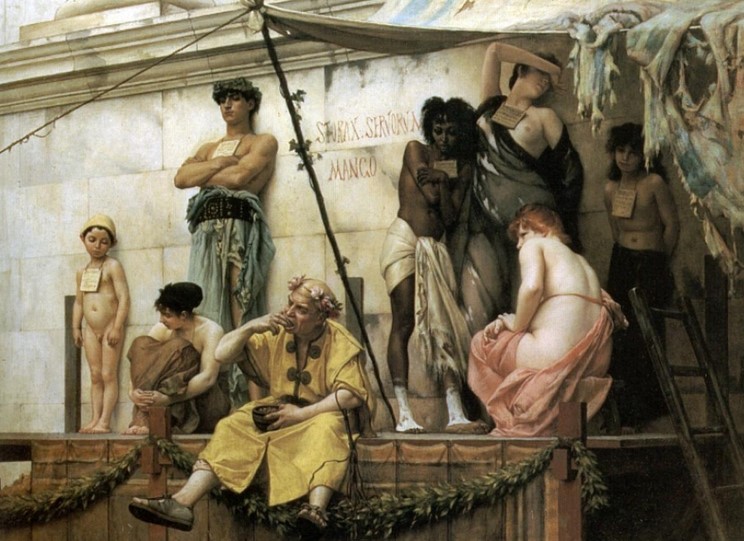

In ancient history, enslavement represented a fundamental component of the economy. All peoples used enslaved people as low-cost labor, often particularly specialized and sought-after workers. The enslaved people were not all the same; they had heterogeneous origins (prisoners of war or pirate raids, children of people in servile conditions, or men who had lost their freedom due to debts) and different qualities (age, gender, nationality, physical appearance, strength, culture, technical skills, and specific competencies). They had in common only the fact that they did not enjoy civil and political rights. In any case, they were considered precious assets, a real commodity whose price varied based on the qualities that determined their occupation.

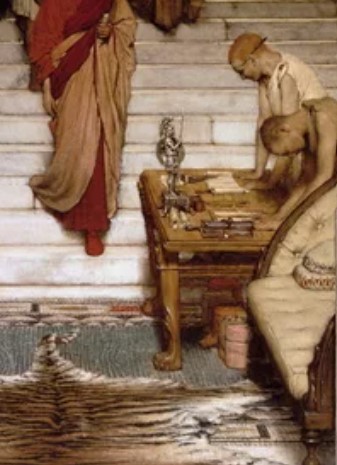

The enslaved people constituted the productive fabric of society. They were employed in various ways: artisans in a workshop, laborers in the fields, miners, or as domestic servants in the homes of wealthy families. Among the latter, educators and wet nurses were particularly respected and appreciated, as they were the real ones responsible for the education and nourishment of children and young people from the best families.

The artisanal sector depended on servant labor: in the workshops of blacksmiths, goldsmiths, and ceramicists worked men trained in these trades.

The absence of certain sources and archaeological finds does not allow us to reconstruct the relationships between masters and servants in Etruria. We only know that whipping was a frequent method of command and that in some domus, relationships were more humane and familial, as evidenced by the elegant and refined clothing belonging to enslaved people (Volterra).

The rich Etruscan civilization was hedonistic, loved the good life, wine, banquets, and luxury, but at the same time, could be ruthless and cruel with enemies who called them pirates, with prisoners, and with servants. The discovery of the Man in Chains demonstrates how among the 'servants' there were even more 'rigid' servile figures, rarely mentioned in ancient sources.

Little is known from sources about the Roman conquest of the city. Certainly, it always enjoyed a certain autonomy because it was an ally of Rome. Thus, it was able to continue minting its own coins and maintaining its trade activities. Only around the mid-3rd century BCE did Populonia experience a brief period of crisis, perhaps following events that brought it definitively under Roman rule.

At the end of the 2nd century BCE, ironworking resumed on the coast between Populonia and San Vincenzo.

In the 1st century BCE, Populonia was under Roman control. It became a municipium and was ascribed to the tribe Galeria, as documented by an inscription recalling the quattuorvir L. Vesonius.

In this century, an episode occurred that marked the beginning of a slow and progressive decline: the internal wars of Marius and Sulla (the first Roman civil war, 83-82 BCE). Populonia sided with Marius (157-86 BCE), who was then defeated; Sulla decided to punish his allies and destroyed the cities. Populonia suffered a siege by Sulla's forces (138-78 BCE) like Volaterrae, and was almost destroyed by the victor. Populonia continued to be inhabited, but lost its prestige and strategic importance, and over time became depopulated. At the end of the century, the Greek geographer Strabo speaks of an almost deserted acropolis (only the temples and some houses were still standing) and the port area still inhabited. It seems that Populonia never recovered from this blow.

In Populonia, besides enslaved people, there were also freedmen, men previously enslaved and liberated from enslavement. An example is Ledeltius, who lived here around 50 BCE when Populonia was a municipium of Rome. We know Ledeltius thanks to an object of his found in the domus where he worked: an unusually intact black-glazed ceramic inkwell, on which his name, LEDELTIVS L T, was engraved. Ledeltius is his Greek name Latinized; the letter L probably stood for Lucius, a very common name at the time; the letter T was the initial of an as yet unidentified gentilicium.

Ledeltius was an servant who managed to regain his freedom. He worked as an accountant and tutor in the house of a political figure of the Roman Republic era, perhaps a magistrate.

Along with the inkwell, some styluses for writing on wax tablets and a fragment of a ceramic doll belonging to a girl from the Roman Republican period were found. This suggests that the freedman was probably also a tutor for the children of the dominus (host).

We do not know where Ledeltius came from. Perhaps he came from the large enslaved people market of the Aegean, where enslaved people were given a new name, Greek, and then somehow arrived in Italy and Populonia, still in a servile state.

The domus where he worked was very large and luxurious, even equipped with a small private bath. It was located under the Logge, in the upper part of the city. The Logge was a monumental building with a sacred character with a facade of blind arches that had a scenic view of the temple area. A stone-paved road, passing in front of the domus, connected the Logge and the three large temples to the city's forum. The road was probably pedestrian and used on solemn occasions as a sacred road, not showing signs of prolonged wheel passage and being steep.

The domus was destroyed by a fire around 50 BCE, during the civil wars that characterized the final period of the Roman Republic. The fire stopped everything at 50 BCE. We do not know what caused it, but it certainly caused the entire house to collapse. It was hurriedly abandoned by the owner and his family because everything inside the domus is still there, not saved or taken away. In the service areas of the house, there are still kitchen tools, the fireplace, portions of furniture like nails and hinges, ceramics for the table and pantry, pieces of terracotta toys, ceramic lamps, game pieces, keys, and locks, in short, everything used daily in a house. The large rooms richly decorated with mosaic floors, the private baths, and the banquet halls where Ledeltius' master welcomed his guests have come to light. Additionally, there were more secluded areas, hidden from the view of external guests and used only by family members.

We have seen how the decline of Populonia began in the 1st century BCE. This was followed by barbarian invasions and looting that decimated the population over the centuries. By the end of the 6th century CE, only its ruins remained where the ancient strongholds were just a memory.

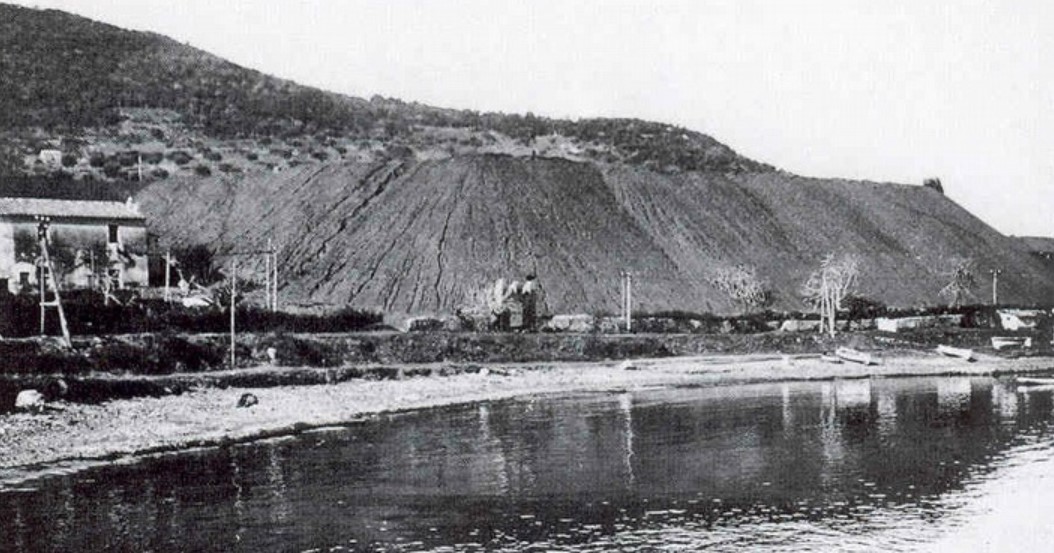

Thirteen centuries later, Populonia was rediscovered by chance. The accumulation of iron slag in the Etruscan and Roman periods around the Gulf of Baratti had buried the ancient necropolises by several meters. In 1897, to recover this slag, the ancient Populonia came to light.

During World War I, the removal of iron slag was intensified for military use. The Latin historian Livy informs us of a similar supply during the Second Punic War. In 205 BCE, Populonia supplied Scipio Africanus with the iron needed for the expedition to Africa. Scipio requested the resources of the province of Etruria to supply his fleet. Each of the main cities provided what they had in abundance: Caere sent grain and other provisions; Tarquinii, sailcloth; Volaterrae, naval equipment and corn; Arretium, grain, weapons, and various tools; Perusia, Clusium, and Rusellae, grain and fir for shipbuilding; and Populonia, iron.

In order to know more:

- Wikipedia: [1]

- The Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria by George Dennis. Published by John Murray, Albemarle Street, London, 1848.

This page was last update on 14 July 2024

Open in Google Maps and find out what to visit in a place.

Go to: Abruzzo | Aosta Valley | Apulia | Basilicata | Calabria | Campania | Emilia Romagna | Friuli Venezia Giulia | Lazio | Liguria | Lombardy | Marche | Molise | Piedmont | Sardinia | Sicily | South Tyrol | Trentino | Tuscany | Umbria | Veneto

Text and images are available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 4.0; - italystudynotes.eu - Privacy